|

|

||

|

Bob Elgas (1920-2010) “One of Nature’s noblemen” |

||

Early on the morning hours of July 16, 2010, our dear friend escaped the bonds of this earth and is now in his wonderful aviary world. glt My first recollections of Bob Elgas was in 1979 when I was asked to be art narrator for a fundraising auction in Bozeman, Montana. So I proceeded to call the various artists to have them comment about things they were not often asked about their artwork. Bob Elgas was just one of those volumes of information which could not easily be put down. We stopped by to see Bob and Elizabeth Elgas. We brought along with us a young man who was a wood carver from Illinois, Jim Hoker.

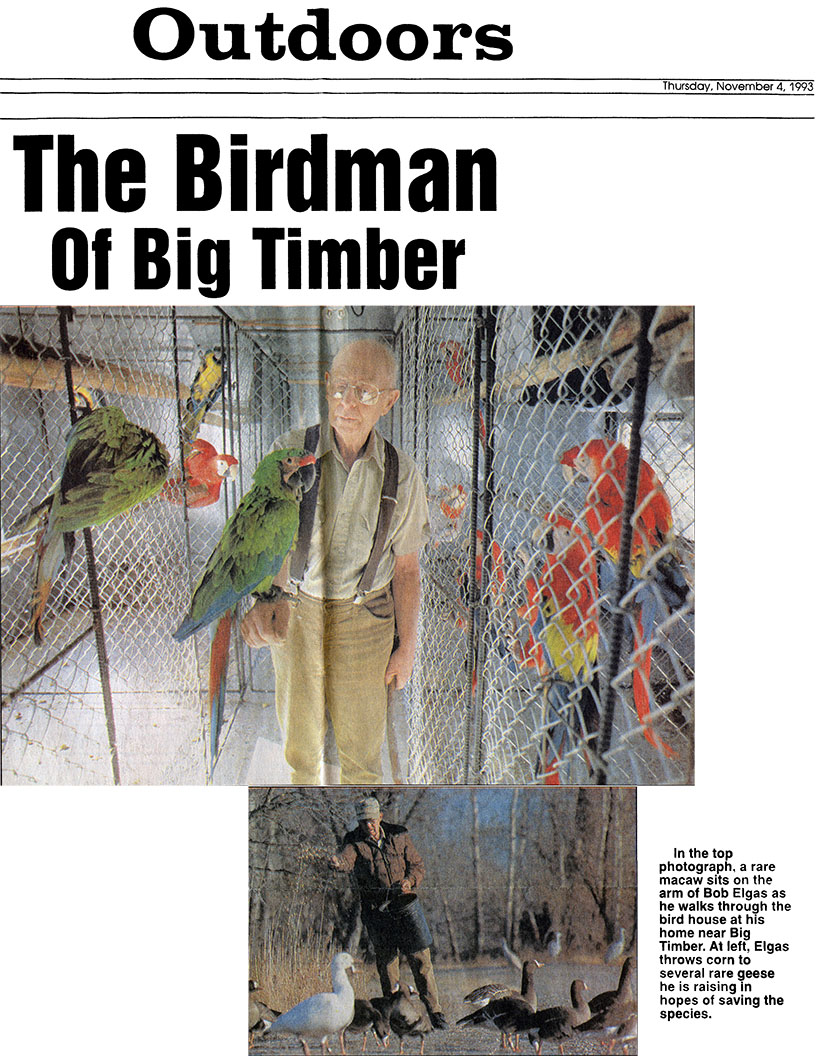

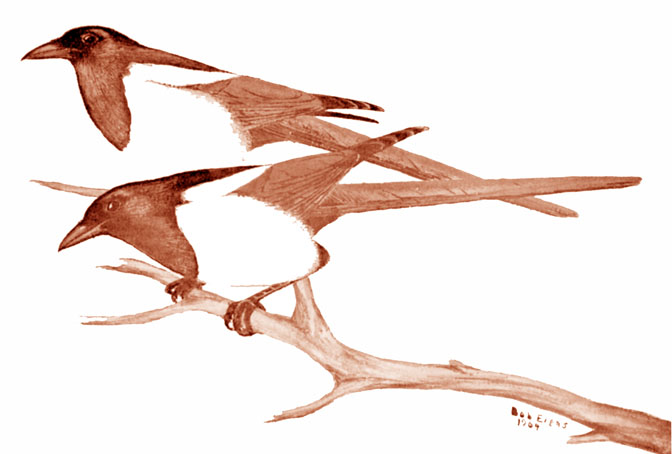

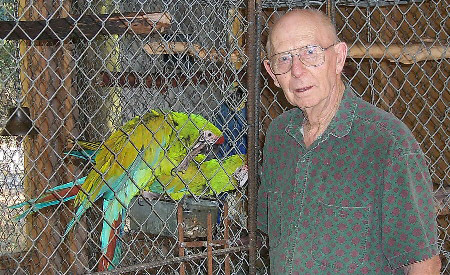

I remember the above photographs fondly for they were taken in the fall of 1983. It was just off the Interstate highway at the rest stop near Greycliff, Montana. But, first I need to go back and explain some facts which come to think about it is very characteristic of all of my dealings with Bob Elgas. All of his explanations could not be done if not being the main purpose of leaving one smiling and laughing at the conclusion of it. It was the Ducks Unlimited banquet in the fall of 1982. An auction item came up for bid but first it had to be again detailed by the Master of Ceremonies, Bob Elgas. I can hear him now just as if it were yesterday. “Now this is going to be a professionally guided hunt by two masters of the waterfowl world, myself and Jim Colpo. We will first sit down to a hearty breakfast sumptuous vitals of the menu world just unobtainable anywhere in this world. Then the hunters will be driven out to a luxurious warm and cultivated blind placed carefully in the field. Topping off the day will include many sips from a selected bottle of homemade apricot wine.” Now how could one not bid on a package offering like this? I remember grinning at my wife, Marylee, when the auctioneer, old Pete Knudsen, sold out to us for $135.00. I can remember the gathering of us after the banquet and laughing about the package but also saying we would be in touch. The following fall, the goose hunting was lean in the Big Timber area so we never connected. The next fall in 1983, Marylee and I came over and stayed with her folks for one night. The next morning we headed out to do some antelope hunting. We came back to the house around noon. We were met with messages from someone calling to find us as it was very important. The messages were from Jim Colpo who then on the telephone told me they had some geese spotted. The plans were set for the evening. Little did I have any idea as to the preparatory arrangements Jim Colpo made for us. They had patterned the geese to one particular field just off of the Interstate. We arrived in the field to find a pit blind big enough for five people. Fortunately there were only four of us but Jim had worked on the pit blind digging away for five hours. Jim had the customary cradle boards set over the hole and then it was covered with stubble from the field to match the surroundings. Their spread of birds, decoys to the non-waterfowlers, were envious to me. I can remember several times how Jim would tell Bob how the blind looked good but he still insisted on getting out to check it several times. Ah yes, let us not forget the homemade apricot wine and a thermos of coffee. The only trouble was we were right out in the open and in full view of the traffic on the Interstate so there was not much allowance for a facility to dispose of the liquids. Finally the calling began by Jim Colpo for out in front of us towards the Yellowstone River we could see the movement of wings. Slowly they banked away from the river and were headed our way. Wary as always, they circled our decoys and finally Jim Colpo called the shot to shoot. We came up causing the birds to turn back behind us but we were able to drop two birds. The hunt was over for the rest of the flock did not return. I still remember Jim apologizing for calling the shot, he felt, a little too early but I thought it was all great. Little would I know how much I appreciated my successful bid for the hunt until years later. Several years ago I started my Customer Percs section on our website. Marylee asked me what this had to do with the artwork and calmly replied, “Absolutely nothing.” Some of the first photographs I put up were the ones from the hunt with Jim Colpo and Bob Elgas. One day about three men came into the gallery and asked if we knew Jim Colpo. They had done a search on the Internet and found his name from our website. I told them, “Know him, I can drive you right to his house.” Turns out they were old high school buddies of Jim and had a great visit. glt Commentary from some friends: I just heard last night, July 3, of Bob being close to his last moments here on Earth. Our thoughts and prayers are now going out to him for his ultimate trip to the bird sanctuary in the sky. Our friend was very special and it was even more painful when he left Montana after Elizabeth's death to move to Oregon. It was not as much the decision to move but it was the inability of many people to visit with him like they did before.glt Some thoughts from some telephone calls to some old friends of Bob Elgas: ~ Comments from Ron Jenkins, click here to play audio. ~ Jim Colpo audio interview, Part 1 and Part 2. Jim Colpo told me about two sayings Bob usually used and how he uses them almost in honor of Bob today. "Springtime in Montana is like a Model T Ford. Just enough spring to make your ass tired." "Sometimes it pays to be so stupid, you don't know you have been defeated." "Bob Elgas for someone who really did not have much of an education was one of the smartest people one could ever run into. I learned so much from the guy. He helped me with my artwork and was really a remarkable man." JC ~ Comments from Jack Hines including audio: Jack Hines said they always referred to Bob Elgas as “One of Nature’s noblemen.” “It really did fit him totally. We used it a lot and with so much respect for Bob Elgas.” Bob used to come over to Jack Hines’ studio before Jessica came out to Montana. He would come over with a color problem and Jack would try to help him out. This was a common difficulty for Bob was color blind. One morning Elizabeth had done her usual thing of laying out the colors on his palette and labeling them. She came home after working at the bank and Bob was busy painting on a Mallard drake with an orange head. He could not tell the difference between orange and green. It was one of those crazy events and if nagged enough he would bring out the painting with the orange duck head. The thing to say about Bob and his artwork was here was a guy who one Christmas was gifted a paint by numbers set. Bob went through a couple of sets and got really interested. He wondered why he could not do this for himself. He had a pretty fairly good drawing capability with an accurate depiction of a species and was right all the way up and down the line. He learned because of his difficulty with color perception to keep things very simple. His painting was kind of monochromatic and caution was used in the placement of each bird. So totally conscientious about it as he was just determined to get things just right. The birds were placed in a very believable situation as he was very careful with any background setting. The background terrain was always correct. Bob never knew how to handle reflections in the water and came to Jack Hines for assistance. Jack Hines said he never met an artist with such integrity in his approach to the thing of painting as was Bob Elgas. He was absolutely a master in species identification and all the little features of the bird. Anatomically and behavior patterns were always correct where he would really get the whole thing going. He was exceptional in his artwork. His parrots were one of his other worlds. Going into the back room one would find them all stowed in their cages. So often the parrots would pick the locks of their cage for the birds were so incredible and very intelligent. They would get out of the cages. Their beaks had incredible strength whereby they almost did chew their way out. He was so devoted to the subject of birds. One day we were chatting and Jack suggested Bob did a couple of ostriches. Bob went wild and absolutely refused for they were dangerous and could kill someone. The comment must have planted an idea in Bob’s head. He and Elizabeth were on a trip and on their way back they stopped at the St. Louis zoo. The man at the zoo was Marlin Perkins. Bob came back with an emu and he was waiting for the second emu to come out. He was determined to have a breeding pair and realized the courting dance was a very important procedure. In the early morning hours people would see Bob out in his yard with the emu. Both of them would be bobbing up and down. Bob would be flapping his arms and the emu was doing the same thing. He was busy teaching the emu the courting dance. Bob in his own way very much looked like one of those birds. It was a sight to behold. Bob and the emu doing the courting dance. “We loved him like crazy. There was nothing one could every be angry at Bob about, he was just one of those sweet kind of people in the nicest sense of the word. People could just find no fault with him whatsoever.” JH ~ Bob Elgas was born in Wibaux, Montana, on January 23, 1920. "Not many other artists have

the opportunity to paint Emperor geese or Sandhill cranes," he emphasized,

"from a flock that eats from their hands every morning, and as a result,

I should be able to-and do-paint them correctly.  (Bob with two of his parrots. Taken in Grants Pass, Oregon. 1999) Another advantage was having had the opportunity to observe waterfowl, and other birds, all over the North American continent. "In 1940, we purchased a cattle ranch. Spent thirty five years raising Hereford cattle until the Interstate highway system bisected the property. A tract of land approximately sixty acres was retained. This is our home, and the acreage has been developed into a wildlife habitat area. Included within our flock are representatives of nearly all the world's wild geese, various kinds of swans, cranes, and other assorted wildlife forms. There has been some scientific involvement as well, including many arctic expeditions. "I did not become involved with art until I was past 40, and this began when I received a paint-by-number set. I do very much regret not having begun at an early age. An additional restraint has been a hereditary color blindness.  (Photograph taken at Bob's home just outside of Grants Pass, Oregon. 1999) I have learned to function within the capability I possess. My palette is very limited and I utilize earth tones that I do see reasonably well. Most people seem unaware that the problem exists." ~

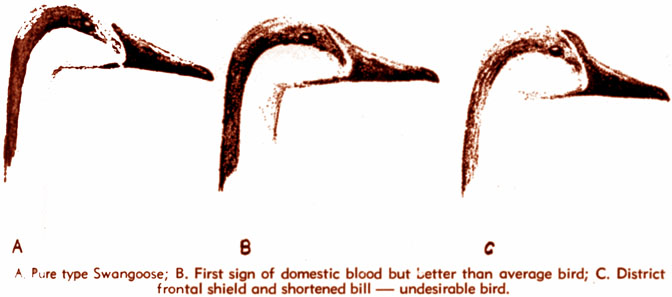

~ For many years, we had been good friends of both Bob and Elizabeth Elgas. During our friendship I threatened myself often to interview Bob about his career and life. Finally, with the persuasive powers of some chocolate chip cookies and hot coffee, Bob allowed me to sit with him and my tape recorder. The following is a close transcript of our conversation over a few cups of coffee and several cookies. GLT ~ My sister sent me this paint by number set for Christmas in the 1940's. It had never occurred to me to paint before, I was too busy chasing livestock. The paint by number set was fascinating with all the little lines and it was fun. When I got done, there was quite a lot of pigment left, I thought it was a shame to waste them. So I just sketched out a goose and as I recall it was a Tule Goose and I painted it. I thought, "Well gee whiz, this was kind of fun." So one thing lead to another and I have just been painting ever since. I never had any instruction. It's just like anything else, if you are determined to do something and apply yourself, you can do a lot of things, you can surprise yourself. Of course, I am surprised, as a matter of fact I am amazed more than surprised because I don't have any natural talent at all. There are two branches of the goose family, northern are known as true geese and those known as brant or brent geese and the difference is very slight. The true geese are characterized by having colored feet and colored bills whereas the members of the brant family always have black feet and black bills. The Canada Goose is a member of the brant family. The two forms are very close together but sufficiently far enough apart if they were to hybridize and breed a member of the true goose family with a member of the brant family it would produce a sterile hybrid incapable of further reproduction. All of the wild and true geese are found in the northern hemisphere as there are no true geese in the southern hemisphere. The southern hemisphere has what ornithologists refer to as goose like birds. I have been interested in wild geese for many, many years and I began to study wild geese and read about them. I was particularly interested in the North American species initially and when I came to the Tule Goose, I found that there was virtually no information available. Very little was written about them and what was written was sketchy. They were almost unknown and so I decided I would like to learn more about them. I began to try and research them. Initially, I should say they are a sub species of the white front goose family. The common white front we have here is anser albifons frontalis. Anser is either Greek or Latin for goose. Albifons refers to the white front or the white ring at the base of the bill. Frontalis is just Latin for front. The Tule Goose was listed as anser albifons gambelli and initially they were described from birds taken by Hartlaub in 1852 in Texas. He described them as a separate species and named them anser albifronz gambili. Hartlaub was an ornithologist. Now subsequent it was discovered the birds were a big, large, dark colored, white fronted goose, different from the Pacific white fronts. A little later it was discovered there were big, dark colored birds over in the interior valleys of California particularly in the Sacramento valley. They were also listed as anser albifronz gambili and called Tule Geese. A man by the name of James Maufitt became interested in these birds and was doing a great deal of study. He collected numerous specimens in the Butte Sink area of the Sacramento Valley. He made substantial recordings, measurements and so on of these birds. He put a number of skins in the University of California at Berkeley. This was along the time period from 1915 to 1917. Maufitt was inducted into the Army and served in World War I where he was unfortunately killed in action. With his demise no one continued his work he had been doing and no subsequent work done. So the birds were essentially forgotten. As I said before, I became interested in North American wild geese and began studying them. I found after you got past Maufitt’s work there was nothing being done. I began to write and talk to various people in the waterfowl field. Various game people with the California Department of Fish and Game, the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Service and so on, the old timers. Most of those people would tell you, "Well, we remember them from years back but we haven't seen them for a considerable time period." Then I discovered the current professionals within the Fish and Wildlife Service said these birds did not really exist for they were just a figment of our imagination. Even though a hunter would bring in one of these big, large, dark colored birds, their opinion was this was just an unusual member of the common white fronted family instead of being a special bird. I was convinced they were mistaken as I kept doing more and more research. And then quite by accident, I got correspondence from a man in Oregon who said he had a live Tule Goose picked up during a storm by a member of the Oregon Game Department. The goose was turned over to him for safe keeping. It was possible one of the members of the Oregon Game Department gave him my name. I got in touch with him and he said, "Yes, he had this big Tule Goose." Bob asked if there was any way that he could acquire the bird from him. He did not see why not as the bird had no real significance to him. So I traded him a Ross's Goose for it. And when the bird came, it was absolutely spectacular. I knew that they were big and dark but I was not prepared for it to be as spectacular as it was. This really did spur me on. This was about the 1950's. This spurred my interest further and I did more and more writing. I came to the conclusion if these birds still existed without a doubt it would be somewhere in the Sacramento Valley because this was where James Maufitt made all of his earlier collections. Early on before I even got into these California birds, I was studying the race from Texas that I mentioned Hartlaub had described as anser albifons gambelli. These were the birds described in 1852 in Texas. During my studies I had made up my mind these birds were what we would refer to as a forest dwelling species. With wild geese there are two varieties, those breeding on the open tundra which are known as tundra nesters and those breeding inland in more forested areas which are forest dwelling species. Basically all of the larger geese are forest dwellers and the smaller ones are tundra dwellers. I had done a lot of study and I had determined these birds were in Texas. The logical place to look for these birds would be on the McKenzie River Delta. The McKenzie River Delta makes its most northerly most penetration into the Arctic of any Arctic area. This would be a logical place to look. I could not finance it myself but I was able to get a financial grant from the Smithsonian, World Wildlife Fund and the International Council for Bird Preservation. The year was 1964, the three of them in combination furnished enough funding to finance this expedition. So we went up to the McKenzie River Delta and did a fair amount of searching without finding much. It is such a vast area and a wilderness of brush and trees. Just by happenstance they had a little softball game there at one o'clock in the morning because it doesn't get dark. We were watching this game and there was an Indian sitting directly behind me. I guess it took him until about the seventh inning to get up his courage and he finally tapped me on the shoulder and asked, "Are you the guy looking for the big, dark, white fronted geese?" I said, "Yes." He said for me to go to the village of the Old Crow over in the Yukon. Ask for Chief Charlie as he was the head of the village. He would show me where those birds lived. We chartered a plane and flew over into the Yukon into to what is known as the Old Crow Flats. We went into the village of Old Crow and I went to the Mounted Police Headquarters. By this time, we had radioed ahead and they knew what we were coming for and had arranged for Chief Charlie to be here. I explained to Chief Charlie what we were looking for and he said, "Yes, I know right where they are. We refer them to as Laughing Geese." We arranged for him to go with us and we went into that area and found those birds. We captured five or six downy babies. Then working with the Canadian Wildlife Service biologist in the area, they brought in a huge big net. They were nets about four feet tall but about three hundred feet long. The nets were set up in a big "V" with a holding pen in the middle like a corral. The adult birds are flightless in the molt. We went out into the big lake where there was about a hundred fifty to two hundred of these big birds. We herded them in with the plane by taxing back and forth with the floats. We brought all these birds into this big impoundment so we could capture them. We weighed, measured, and evaluated those birds and then we put Fish and Wildlife Service bands on about seventy five birds which were then released. We took eight or ten live ones back to Montana and also some were sent to the Petuxent Wildlife Research Center for their ornithological staff to evaluate. After they had evaluated them, they said there was no doubt but what these were the birds we were searching for, Tule Geese. We wrote an article in conjunction with John Aldrich, their Chief Ornithologist, and this was published in the Wilson Journal which is one of the lead ornithological bulletins in the United States. Then we sat back, waiting for band recoveries which we were sure were going to come from the central valley of California. Well when the band recoveries started to come back in the fall, all of the band recoveries came from Texas and northern Mexico. These were the original gambili that Hartlaub described in 1852 which meant the California birds were an undescribed race because they were different. So we had established these gambili white fronts were Hartlaub's original birds and set distinct from the California birds. So I wrote to the Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington, D. C. and asked for permission to go to the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge and work in cooperation with their refuge personnel. I as a private individual and they as members of the Fish and Wildlife Service in an effort to see if we couldn't learn something about these birds. Well, ultimately I got a response from Washington, D. C. saying we had never received this type of request before. They did not even know how to respond so they said what they were going to do was just turn your request over to refuge manager at the Sacramento Refuge and let him make the decision whatever he says. So then I got word from them to go out to the Sacramento Refuge and work with their people. The refuge manager was Ed Collins and the refuge biologist was Dick Bauer. After I got there, we really hit it off well and became really good friends. We are still very close friends. Ed said to me one day after we did get to know one and another well, I ought to tell you the story when I got this letter asking if you could come to the refuge. It had been a bad day and I looked at the letter and I thought the last thing we needed out here is some guy from Montana kicking around, stirring things up and making extra work. I sat down to write back to say we were not interested but maybe I should wait to morning and talk to Dick, the biologist. Well when Dick came in the next morning, Ed showed him the letter and said, “Dick what do you think about this?” Dick said, “I have been out there on the grounds quite a lot and there's something different. I don't have time to go out there and spend a lot of time studying. I am convinced there are some different birds out there. Why don't we let this guy come out, take a shot at it and if it doesn't turn out we can just send him home.” So they said okay, come on out and so I did. It wasn't more than a few hours before I realized that there were two different birds and one of them was most certainly these big Tule Geese. Well they brought in a lot of their people, and biologists from around. The state man came in and the waterfowl coordinator for the State of California, Bill Anderson was his name. They were really nice guys and said, "Look you're barking up, you're just wasting your time, these birds simply don't exist." Bill Anderson said, "We have Audubon bird watchers out here all of the time and if there was a different bird out here there would be no way you would get it by those people without them seeing it.” Bill Anderson who was the Chief Ornithologist for the State Of California had told me over and over again these birds did not exist. He felt if they did exist they would be picking one up every now and then, but they were not. I said, "Let's go down to Berkeley and look at the skins." He took his whole staff and we went down to Berkeley. Now these are the skins that James Maufitt collected about 1917. They had been sitting in that museum and the drawers probably had not been opened for over fifty years. We opened those drawers and Bill Anderson said, "I absolutely can't believe what my eyes are seeing here. I can't just believe this is true.” They had skins of Pacific and common white fronts. When you compared the two it was like placing a grape beside a lemon. This was during the early days at the Sacramento Refuge. At about the time I had just started at the Sacramento refuge, they took me over to Grey Lodge which was the refuge managed by the State of California. The Sacramento Refuge was a federal refuge. The manager there was very friendly, he said, "Look these birds simply do not exist. I am absolutely confident they don't exist. I am glad you are here but if you can prove me wrong, I'll give you every bit of help that I possibly can. They don't exist but if you want some help just call on me.” We went back to the Sacramento refuge and determined there was no question as to the identification of the birds. Sacramento Refuge is a good sized refuge but it is split into two parts. The western part was planted in several thousand acres of rice. The birds harvest this rice. The eastern half is much smaller and was full of dense bull rushes. They are like cattails but much taller. The Tule Geese lived in these bull rush impoundments and never went to the open lands. All of the water in the refuge is manufactured, they turn water in and make impoundments and put dikes up to hold them. The eastern half has grown up to these immense tall dense bull rushes and this is where the Tule Geese lived. The white fronts are over on the west half and the two never intermix. They just don't have any affinity one for the other at all. I could see obviously these birds were there. So then we determined in order to prove they were there, it was going to be necessary to live capture them so we could have the ornithologists from the Fish and Wildlife Service, I mean their true experts have birds in hand to evaluate. Well we discovered normally when you want to catch wild geese all you do is bait an area, then use rice because it is their favorite food and after three or four weeks the birds regularly come to it. Then set up what they call a cannon net. It is a big net about seventy five by sixty feet which is fired from three cannons. You fold the net and then have the baited area in front of it and then when the birds congregate, you fire the cannons electronically and this net flies out over them and catching them. Well, we discovered Tule Geese would not respond to bait because they were not feeding on rice. They just were eating the tubers or roots of the bull rushes right out in the impoundments. So we could not bait them so what we endeavored to do was set up platforms out in these impoundments. This was very difficult because it involved working hip deep in water trying to build a platform to furl or fold these nets. Also they needed to support the cannons fired from them. It was a big job to just set a net and then there was no way of baiting it. We just set it and hoped some geese would come and sit in front of it. Of course, there are hundreds and hundreds of acres for these geese to be and it took us five or six years before we could actually catch some because it was just hit or miss. I came back to the Sacramento Refuge each fall and we had several disappointments along the way. For example, we would set a net. The Tule Geese would come and sit about fifty feet in front of it or just to the right or just to the left or maybe behind it. Everywhere other than where they had to be for the net. But finally we got a nice little bunch in front of the net and of course we had set dozens of nets in different locations. We fired the net and it was a brand new net. The net had been tied up along the furling to keep it neat. One of the guys in helping to set the net, failed to untie one of the ties. So when you fired the net it was tied fast and could not unfurl. All which happened was a big blast with the end of the net going out in the water. The geese flew away. Of course, this is really heart breaking but ultimately along about the fifth or sixth year I discovered there was a substantial flock of about seventy five of these Tule Geese coming in to one little impoundment to spend the night. This was a very small puddle about one hundred feet long by about sixty feet wide. So I told Ed Collins the refuge manager what we had and he said, "Boy this is too good to lose. What I am going to do is call the State of California because they have two immense cannon nets one hundred feet long by sixty feet wide. We can set one on either side of this lake and we can cover the whole lake or pond.” So they sent the two cannon nets over. Normally a cannon net is seventy five feet long and is fired by three cannons and has a wiring harness to fire it. Well these were one hundred foot nets so they put four cannons on it. They then had put a "Mickey Mouse" wiring harness to go with it but they didn't send any instructions on how to do it. We thought we knew how and we set it up, got it all ready. Evening came and just about dusk these geese came pouring in. The flock was about seventy five or eighty. I touched the detonator and the number one cannon was the only net which fired and the geese flew away. I was just virtually sick to my stomach because this had been like seven years. So I went back and told Ed what had happened. He said, "Oh nothing could be worse, just some little mechanical failure but I'll tell you what we will do we will go out again in the morning and reset those nets. I will take Johnny our head mechanic and we'll make certain that those nets are properly set.” We set the nets and went over every circuit. We were now set. The evening came and the geese came back and I fired. The same thing happened again with the number one cannon. So I went back with tears in my eyes. Ed said, "I don't know what to do and I am going to call the cannon man from the state. So he called him and the guy said I know exactly what's wrong, I'll be there in two hours and we'll set those nets in the morning. We will set them so they will fire.” So he came showed us what was wrong. He said, "The way you had them wired when you pushed the plunger on the detonator it would fire the number one cannon, then if you would have pushed it again twice then the rest of them would have fired.” They all needed to fire at once so he went out and wired it correctly. The next evening only eight birds came in because they had had enough. Ed Collins was with me and when the birds got in front of the net, the cannon net caught all eight of them. We took them in and we had holding pens ready at the refuge headquarters. By the time we had caught them it was dark and we couldn't see them at all. But as soon as we got them in there, Ed Collins said, "I just can't believe these big, immense, dark colored birds. I would have never believed it." So the next morning he sent a wire to Washington, D. C., to the Director of the Fish and Wildlife Service about catching the birds. My goodness, we got letters, and wires, and telegrams of congratulation. We drank champagne, we did everything. We sent these birds to Washington, D. C. to the Patuxant Wildlife Research Center for evaluation. The birds were accepted as valid and they could no longer argue the birds did not exist. They did exist as we had live ones in our hands to prove they existed. We did a lot of other work, we captured more birds in an effort to learn more about them. This was when radio telemetry was in it's infancy. We put radio transmitters on these birds but it wasn't sufficiently sophisticated for it could only send signals about eight to ten miles. We imped in white feathers on one wing. Imping is an old technique coming from the ancient falconers where when n a feather was broken they transplanted a new one. They would cut the shaft off where it emerged from the body and put a little hardwood dowel like a toothpick in there. They would cut a corresponding feather off another bird and just glue it in to rebuild the feather. We took white wing feathers from a snow goose and put in a whole speculum of white feathers on these birds. We then released them with radio transmitters. One could visually track them all around the refuge by the white wing feathers because they just loomed out. We were not successful in tracking the radios. Actually, I flew to Alaska and flew thirty or forty thousand miles trying to pick up radio signals but was not successful simply because the transmitters were not durable. In the mean time, unbeknownst to me, Dr. S. Dillon Ripley who was the Secretary of the Smithsonian and Jean Delacour, who were probably two of the foremost ornithologists in the world as it refers to waterfowl, made a description of these California birds. Now the Texas bird were known as anser aberfron gambili, which stayed with them. But they described these California birds and named them anser albifron elgasi, which I thought was very unfortunate. I did not even know the description was being made until it was done by the American Museum of Natural History. The American Museum of Natural History sent me a copy of the publication with the description. I still think it was unfortunate, they should have named Californiai because they are absolutely indigenous to California in the winter. Be it as it may I was not a willing participant in the decision of the name. The Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington, D. C., put out a directive to all of their people on the Pacific Flyway, especially in Alaska. It asked them to be vigilant at all times for anything which might help them lead to the unknown breeding grounds. At the same time, I continued to do all my own research to the best of my capability and I was in contact with a lot of people in Alaska, even Fish and Wildlife Service people. I kept getting reports of these big, dark geese; fragmentary reports, one now and then again here. But almost every instance they pointed to Cook Inlet. Cook Inlet is the big inlet which comes from the sea into Anchorage. Bit by bit, we kept getting more and more and more information and again all focused in the Cook Inlet area. Then in 1978, we had our International Wild Waterfowl Convention in Pennsylvania. I had a good friend there I had known for many years who also was interested in the Tule Geese and the work we had been doing. When we came into the convention, he said, "Hey I've got something to show you." He brought out these series of photographs and said "Look at these!!" I said, "Good heavens these are Tule Geese, where did you get these?" He said, "There's a man in Alaska. I've got his name and address for you. He captured these birds as babies and he did not know what they were. He had no idea other than they were geese. He doesn't even know they were white fronted geese, he just knows they were geese. I will give you his name and address so you can get in touch with him." So I wrote to the man and he was very good and wrote back how he had found those birds up on the North Shore of the Cook Inlet. He had raised them as babies. So I went to Warren Hancock who had financed a lot of the private work I had done because it was beyond my capability. I went and showed these photographs to Warren, he said this was enough to put together an expedition to go into the Cook Inlet area and see if we can't find these birds. So I wrote to the Fish and Wildlife Service in Alaska and asked for a permit to capture white fronted geese on the North Shore of the Cook Inlet. They wrote back and said, "Yes, that they would issue a permit for twelve." Well, the permit didn't come and I wrote back and they said, "Yes, it was in the making and we will get it to you." This went on and on with the permit not coming. Finally it was about time to go, so I called them and they said, "Well look, you just come ahead and the permit will be on our desk waiting for you." So we went into the Fish and Wildlife Service when we got in there. It was just like everything had changed, they were just as cold as ice and said there was not going to be a permit. I asked "Why?" They there just was not going to be a permit. They wouldn't give a reason, they wouldn't do anything, they just said there's no permit. I was absolutely furious. Gary: Did you ever find out why? Elgas: Well, I only have an idea. The idea is they began to realize there was something important going to happen and they didn't want some yokel from Montana doing it. They wanted one of their people to do it. So that's why they refused the permit. Anyway, I said to Warren, as long as we were there we were going to go in and look. So we chartered a light plane and went into this area. We did a lot of flying and were coming down the Big River which is one of the rivers flowing down into the North Shore of the Cook Inlet. Just about a mile inland from the inlet itself there was this flock of about seventy five adult birds with about seventy five half grown goslings all in a big bunch out on a mud flat. No question what they were, absolutely no question. We flew around and Warren is a good photographer. He probably took two or three rolls of film. And when he got done taking pictures I asked the pilot, "Put me down." Warren said, "What are you going to do?" I said, "I have to go the bathroom." As soon as we got down, this was a big open tundra with a river running through it with channels. I peeled off my clothes and I took off after those birds. I said to myself, I have been working twenty five years on these birds and I am not going to lose this now just because these yokels would not give me a permit. This is too important, I spent a great deal of my life on these birds. So I went in and caught six of them. Warren would never do anything wrong and he was about as honest as possible for a human being to be. If it said don't spit on a sidewalk, he would strangle rather than spit. Once I caught them, Warren fell into the spirit of things, he was tickled to we had them.

I brought them home and I immediately notified the Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington, D. C., we had found and captured these birds. I did not tell them we had bought the live birds back. I told them we had found them. I notified the Fish and Game of the State of Alaska in Juneau, and told them the same thing. I turned these babies loose in my side yard. I had about seven or eight wild caught Tule Geese from the Sacramento Refuge. When I put those babies in the yard, those wild geese just went berserk. They wanted to get to those babies. So I finally thought well I will turn them in and see what they will do. I turned them in and they just mothered those babies immediately. I also had common white fronts and they didn't pay attention to them at all but the Tule Geese did. Of course, I knew them to be the genuine thing but this was absolutely the clincher. When I called Washington and told them about the discovery, they said, "Alright, this is what we want you to do. If you will go back to Alaska and take one of our people and show them what you found. We will guarantee a permit to capture some." I said okay. Now when we, Warren and I, made the initial discovery it was on the third day of July, 1979. We went back just about a month later and they had chosen Dan Timm. He was the waterfowl coordinator, the chief waterfowl biologist for the State of Alaska. This was the man we were to take in to show. The day before he came over to our motel room and we talked all afternoon about the studies we had done and so on. One of the things that he said, "You know its odd, last fall I went into the same area hunting. I shot two of those birds and it never occurred to me what they were. I did not think anything about it." We went in and showed him the birds. We caught eight or ten birds and brought them home. Dan Timm issued a press release which was carried by all of the major papers in the United States and some over in Europe. "This long sought after discovery had finally been made after years and years of not knowing. They had discovered the breeding grounds of the elusive Tule Goose and Dan Timm had made this discovery accompanied by a rancher from Montana." While he was making his press release, Audubon Magazine sent their editor to do a story. They did a huge layout complete with photographs and a description of the discovery. It came out just shortly after Dan Timm issued his press release. Of course, it was in direct conflict with the announcement by Dan Timm. Dan Timm was furious, he notified Audubon Magazine about the material was not factual. He said, "To begin with Elgas is nothing but a farmer. He doesn't have the capability to make a description like it, only I, a trained biologist would have the capability so his description is invalid." Audubon called me on the phone and said, "Hey, we are getting all of this flak from Alaska saying our article is not factual. What about that?" I said it was factual, I can show documentation to prove it. So they sent the Editor out again and they reviewed the article. In the next issue of Audubon, they put in a little piece saying there was some controversy over the article and the authenticity of it. We have reevaluated and found the article was correct as written and we stand by it. Dan Timm was absolutely livid with rage. To refer to the career of a man in the service this way, to make a major discovery like this, I mean it is going to escalate him to the very top. It would mean recognition, advance in pay, advance in stature, the whole bit and he wanted it. Due to this there has always been some bad blood between us because he didn't think I should question his discovery because he said I was just a farmer. How could you have the capability of recognizing a race? Well, he could recognize where he shot two of them and didn't realize what he had. Dan Timm to this day is recognized as making that discovery of the breeding grounds of the Tule Geese. He is recognized by the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the State of Alaska. I objected to the State of Alaska because he was a state man. The Director of the Alaska State Fish and Game Department wrote back and said, "Well, what happened was really unfortunate but we are not going to change it." Within the professional circles, he is still credited with making the discovery because I have no way of getting my story out and he's writing all the time. Sometime later, I gave Dan Timm a little credit. They were concerned about the breeding area on the North Shore of Cook Lake Inlet because there are substantial oil reserves in there. There is a lot of oil exploration in the Cook Inlet, a lot of oil derricks, and they were really concerned the oil companies would go in there. They felt they would exploit the land and it was a very small area. This could be devastating to the Tule Geese population. The State of Alaska decided we had to get this set aside as a refuge area to protect it. The oil people were fighting tooth and nail not to have this happen, they wanted to get in there. Dan Timm wrote to me then and said, "We have our differences, in the interest of these birds, would you work with me in an effort to convince our State Legislature the importance of setting this area aside." I agreed. What we are going to do is put a big article in Alaska Magazine pleading the case for these birds. If you would work with me I think we can get it done. We sat down and between the two of us we wrote an extensive article and in the article, he prefaced his part by giving me a lot of credit for the work I had done. Before he had never given me credit for anything. At the time he had given me credit for all of the work I had done except he did not mention the discovery. He did not say he had discovered it, he did not mention it. We wrote the article in conjunction and we were successful and the legislature set that area aside. Everything I have told you is actually factual, I haven't sided it one way or another. If you were to ask Dan Timm, you would get a totally different story, but his story would not be true.

Bob's "Thumper"

~ The following are from the Modern Game Breeding magazines, courtesy of Ron Jenkins. Modern Game Breeding

January, 1965 Although the Tule Goose has been known for at least half a century it has remained a bird of almost complete and total mystery. Probably never an abundant species, it has been known to winter, in very limited numbers, in certain areas of California – notably Butte Sink and Napa Marsh. Most records and collections of Tule Geese have come from one or the other of these locations. The breeding ground has remained unknown and certainly this bird is one of the rarest species of wild geese existing in the world today. My own interest in the Tule Goose has been of many years standing. In an effort to be availed of all possible information, contacts have been made with waterfowl specialists, biologists, various game department officials and, in fact, anyone who might possibly have a shred of information in regard to this bird. In addition, as much printed material as could be found was assembled. The search for information has continued, until gradually a few pieces of the puzzle have been fitted together and at last what might be considered a hint of an overall picture has resulted. One fact that became evident very early was that the Tule Goose was in serious circumstance. Numerically so rare, that even in areas where it was supposed to congregate it was virtually unknown. If the bird was to be preserved for future generations it was obvious that an effort had to be made in its behalf. In order to inaugurate effective protective legislation, it was most important that the nesting ground be found, for in this way, by utilization of a banding program in the northland, it would be possible to learn migrational routes, stopover points and concentration areas, so that appropriate protective measures could be taken. To undertake the task of trying to locate the nesting ground of so rare a bird, in an area as vast as Arctic North America, seemed hopelessly impossible. However, if help was to be given the Tule Goose, it was a job that needed to be done. Although the nesting ground was unknown, a thorough evaluation of evidence indicated the most logical place in which to expect to find nesting Tule Geese would be the MacKenzie River delta area of Western Arctic Canada. Here it was decided the search must be made.

Once the decision was made the big problem was that of financial support, adequate enough to allow a sufficient search of the MacKenzie area to locate the elusive birds. One of the leading organizations in conservation, World Wildlife Fund, approved sponsorship of the MacKenzie expedition, and a $3,000 grant was made available. The purposes of the expedition were to try to locate nesting areas of the species to band adult birds and to obtain young birds for a propagational program. These young birds would be used in an effort to produce a captive flock, against the day when this wild goose could disappear from their native haunts forever. Under the stewardship of World Wildlife Fund, and with field support from the Canadian Wildlife Service and the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the expedition had at last become a reality. For me this was the culmination of many years of study, hundreds of hours of letter writing and an unceasing search for material and information to make the expedition possible. While it was an occasion for great optimism, the weight of responsibility was not light. Not only had World Wildlife Fund entrusted me with this expedition, buy many individuals and agencies had spent much time furnishing material and vital information. To each there was a great feeling of responsibility for the fulfillment of the project in which this trust had been given.

The expedition, which consisted of Elizabeth and myself, assisted by Jack and Viola Kiracofe, of Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania, began officially on the last day of June when we left Big Timber and headed north across the great wheat country and grasslands of Montana and Alberta. At Edmonton automobiles were abandoned in favor of a Pacific Western DC-6 airliner, which rapidly traversed the vast expanse of wilderness of central and northern Canada, across the Arctic Circle, to the great delta where the MacKenzie River empties into the Arctic Ocean. Our flight touched down at 4 P. M. on July 2nd, at the airfield at Inuvik, Northwest Territories, and the search for the Tule Goose was underway.

At the field we were met by Dick Hill, Manager of the Canadian Wildlife Service Research Laboratory, who drove us the 7 miles from the airfield to Inuvik. Here we were soon ensconced in a very lovely and modern 5 room apartment, which had been arranged for us by Dick’s wife, Cynthia. The apartment, complete with wall to wall carpeting, electric washer and dryer, refrigerator and stove, in view of past, rather placed us in the lap of luxury. The final touch was a beautiful electric console organ, to which unfortunately, none of us could do justice.

Inuvik is a very new town, first established in 1954. The population is slightly over two thousand and is almost equally divided among Eskimos, Indians and White folks, all living and working together in complete harmony. Here the northland hospitality is warmly given and “outsiders” are immediately accepted. The town was established as a focal point for administrative purposes for the western Canadian Arctic and, as might be expected, is a tremendously active community. The Sir Alexander MacKenzie School is one of the largest buildings in Inuvik, completely modern and extremely impressive. Here children are brought from all parts of the western Arctic and educational opportunities are available to them that the older generation did not have. A completely modern 200-bed market hospital is there, as is a large super market, hotel, bank, theatre and many various governmental and administrative buildings. Four different flying services operate from Inuvik, and there are aircraft in the air almost constantly.

Since waterways are the highways of the north, the town was built on one of the main channels of the MacKenzie River. All aircraft are float-equipped for local service. Most heavy supplies are brought down the MacKenzie by barge from Yellowknife, some 1000 miles to the Southwest. The town of Yellowknife is highway-connected to Edmonton, and this is the source of most supplies coming into this part of the western Arctic. Edmonton is sort of “home base” for the folks at Inuvik, as well as most of the surrounding areas. Geographically, Inuvik is roughly 2500 miles north of Seattle, Washington and about 200 miles east of the northeast border where Alaska and Canada join. Climate is dry, with an annual rainfall of about 12 inches. Winter temperatures plunge to 60 below zero, but snow-cover is reported not to be excessive. Summer temperatures are variable. For example: the high on July 4th was 39 degrees, but two days later it was 85 degrees. We experienced a number of days of cool weather, especially when north winds drifted heavy clouds and fog, which had risen from the ice pack on the polar ocean, southward into the delta area. Generally speaking, however, it was warm and sunny, with temperatures much like one might encounter at home. One important difference, we soon discovered, was that the sun shone day and night, with the result that temperature variation was not great. It was almost as warm at “night” as it was during the day. During our stay there was no darkness. This is truly the land of the midnight sun, which we were to see often, and which is one of the most pleasing phenomena of the northern latitudes. Our first day was utilized in getting settled. Elizabeth and Viola took care of this while Jack and I spent the date at the Canadian Wildlife Service Research Station. Dick Hill introduced us to Tom Barry, Resident Biologist. Mr. Barry, who soon became known to us as Tom, is one of the Canadian Wildlife Service’s top Ornithologists. Specializing in waterfowl, he has worked the entire North American Arctic, from the west coast of Alaska to eastern Baffinland and probably knows the Arctic, and its birdlife, as well as any living man. Most of the day, as well as much time during our stay, was spent in conference and consultation with Tom Barry. His help was invaluable to us.

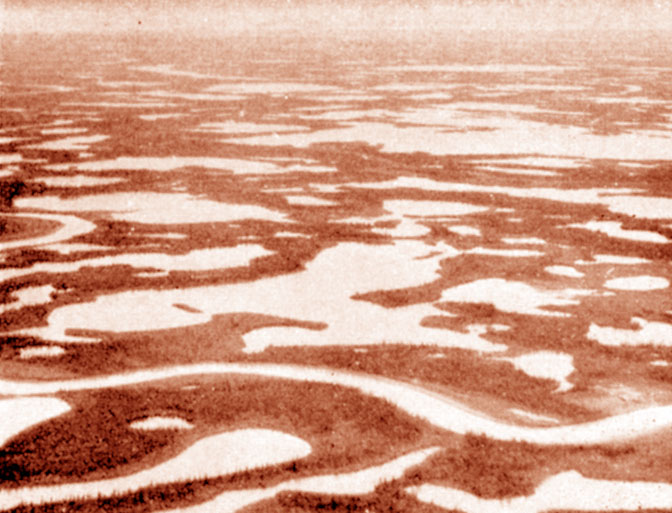

After a thorough discussion, it was decided that a preliminary examination of an area some 150 miles to the westward, known as “Old Crow Flats,” was indicated. This area, which is roughly circular in shape, is bounded by mountains on all sides, and is a vast wilderness condition characterized by thousands of lakes. More important, however, was the fact that it is sufficiently isolated from the main breeding areas of the White-fronted Goose, which are commonly found nearer the coastal plain, to produce a distinct form such as the Tule Goose. Although air counts in the area had previously indicated that White-fronted Geese were resident there, these counts were not made from a sufficiently low altitude to enable sub-specific identification. No information as to exactly what type of geese might be found there was available. Late in the afternoon, Tom took us to the river front to discuss our flying needs with the Reindeer Flying Service. There we met Walter Goulet, who was to do all our flying for us during the search. Walt, who was an exceptionally well qualified pilot, with many thousands of hours of flying time, was subsequently to prove an invaluable member of our team. Without his services we could not have hoped to have undertaken our project. It was soon decided we would make a try at crossing the mountains to Old Crow Flats next morning, so it was off to bed early, in hopes of a big day tomorrow. It did not materialize, however, because the heavy, low clouds over the Richardson Mountains were such that we could not get through to the Flats. Two abortive tries were made, and each time we were forced to turn back due to impenetrable overcast. We did get a good look at the MacKenzie delta, however, and for the first time we began to realize just how formidable a task lay before us. From the air we could see the delta, which was many thousands of square miles in extent, and characterized by literally hundreds of thousands of lakes, interspersed with countless twisting channels and rivers, all winding their way toward the polar ocean. The land area was a wilderness tangle of scrub willow and alder, which we later learned was from 5 to 10 feet in height and almost impenetrable. To find a bird as rare as the Tule Goose in such a jungle wilderness would be hopelessly difficult. The problem was intensified by the fact that the heavy growth extended all the way to the water’s edge and virtually no grassy areas in evidence anywhere. Certainly the old “needle in the haystack” adage could be well applied here. We returned home quite over-awed at the vastness of this wilderness and certainly filled with apprehension for our mission.

Next morning the cloud cover had lifted and by noon it was sufficiently clear to cross the mountains. We at once set out – Walt at the controls of the Cessna 170 (mounted on floats) and Jack and I eagerly acting as observers. The flight over the Richardson Mountains was a thrilling experience. Rising from the coastal plain to a height of over 6000 feet, they presented an appearance quite unlike the mountains found here in some southerly areas. Completely devoid of timber, they were heavily over grown with what appeared to be moss and lichens, and from every inch, even the steep sides, water glistened. We wondered at this, but learned that the permafrost does not allow the water to enter the ground and as a result it is constantly at the surface. Caribou trails were everywhere, though at this season the herds were somewhat farther to the north. In due time we were across the mountains and before us spread Old Crow Flats. A flat plain, surrounded by mountains with thousands of lakes and ponds everywhere. We had previously anticipated a rather grassy open area, but the “bush” was almost as thick as that of the MacKenzie itself. From the air we could see numerous pairs of Whistling Swans, many still on eggs; assorted ducks, surprisingly (to us at least) we saw perhaps 50 or 60 moose, including a number of huge antlered bulls. We were also amazed to see a number of Grizzly Bears, which were the big Barren lands or Tundra Grizzly, which is almost a straw color. In size and ugliness of disposition, however, we learned they are quite the same as the Grizzlies we have here in Montana. During our stay we saw perhaps a dozen or fifteen of these huge bear. Disappointingly enough, our rather careful search of the flats disclosed very few geese, which was cause for considerable concern. One small flock of perhaps a dozen was sighted, whereupon Walt put us down, enabling us to capture two. This was not difficult since the adults were in the moult and flightless. These two birds were of unusual interest, despite their moulted condition, which did not allow for suitable measurements. Both were females, rather too large for typical White-fronts, with unusually large bills and possessing the dark plumage as characteristic in the Tule Goose. Since we had been flying for a number of hours and fuel was low, it was necessary to fly to Old Crow village, some 40 miles south of the flats to refuel. There we were met by the resident Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer, who, upon learning of our project, suggested we talk with Chief Charlie (Charlie Peter Charlie) who was head man of the village. We soon learned Charlie had spent his entire lifetime in the area and knew Old Crow Flats with the familiarity that comes from many years of intimate study. We explained our project and he outlined in pencil certain localities in which to search. The Indians refer to the White-fronted Geese as “Laughing Geese” (from their high pitched call suggestive of laughter). Charlie marked one particular lake on the map, in the southwest corner of the flats, telling us to search this lake and those in the near vicinity, and we would find these birds. During this discussion with Charlie, Walt was refueling the plane so once again we were able to take to the air and return to the Old Crow Flats. With the assistance of the map Charlie had given us we soon found the indicated lake, which he referred to as “Dry Lake.” Immediately we began to see “Laughing Geese,” just as Charlie had told us. It was amazing inasmuch as the habitat was exactly the same as the surrounding area in which the geese were notably absent. Choosing a good spot, Walt put us down and we were successful in capturing two newly-hatched young. Unfortunately, in the scramble we were not able to get a good look at the parent birds, although they did appear unusually large. The downy young were exceptionally dark, particularly about the head, but since young Tule Geese have never been described we could not make a definite conclusion as to their true identity. Judging from other varieties this could be important, since pale colored birds tend to have light colored goslings and dark birds usually have darker young. These goslings could well be the rare birds for which we had come so far. Fueling again was low, so with considerable reluctance we headed back across the mountains to Inunik, convinced that further search and study in this area was of utmost importance. The two little goslings, snuggled down beside us, were soon turned over to Elizabeth and Viola, under whose watchful eyes they were soon happily eating and drinking. Next morning it was back to confer again with Tom Barry. His interest in our project equalled our own and once again it was discussed thoroughly. At this point we decided a look at the Kugalik and Anderson rivers, some 150 miles to the eastward, would be worthwhile. In these areas Tom had done extensive banding and indicated that such species as White-fronts, Lesser Canadas, Lesser Snows and Pacific Brant would be common. Here Tom’s records showed that an occasional “outsize” White-front was encountered, suggesting the possibility of a Tule Goose in this area also. About 2 P.M. we were once again in the air, Walt at the controls and Jack and I at observation. At once the scrub brush of the MacKenzie delta began to give way to more typical tundra country. The tree line makes its northerly most penetration on the MacKenzie, and as we flew northeastward we soon left the bush behind. As always, however, the countless maze of lakes was constantly below us. Our first stop was on the Kugalik, a fairly large river with a rather sluggish current. Here we found a number of low grassy islands – typical goose habitat, and well populated with numerous flocks of Lesser Canada and White-fronted Geese. We did not land but decided to go on to Anderson River and stop on the way back. In due time we reached the Anderson, which disclosed a vast mudflat delta area on which many thousands of ducks, geese and swans could be seen, including many with broods. On the east bank of the river, which was much larger than the Kugalik, was the Canadian Wildlife banding station. Here each summer, Tom Barry brings a banding crew and bands several thousand birds. We had lunch at the station, a very comfortable five room building, typically manlike, but neat and cozy. After lunch we fueled the plane from tins of gas we had brought with us, and headed for the northwest side of the river. Here Tom had indicated we might collect young Pacific Brant. Two rather small side streams entered the river at this point luckily enough we were able to catch our young Brant.

Once again in the air we flew northward about five miles, out over a tiny peninsula – just a small finger of land reaching out into the Arctic Ocean. On this land strip was one of the Dew Line Stations (Distant Early Warning) and we could see their huge antennas and listening devices clearly. Walt talked to them by radio and informed them we were searching for “dicky birds.” From the air we could see the great ice fields of the Arctic Ocean, which was still quite covered with the ice pack. The larger lakes were also solidly frozen, despite the season of the year. Here we saw Sandhill Cranes with young, but due to the ice on the lakes we were unable to land so could not collect them. Here, too, we saw our first Reindeer – big buff colored fellows, with great racks of antlers. We had hoped to collect King Eiders but because of the ice conditions it was not possible to get down and no Eiders were obtained. On the return trip we stopped at the Kugalik River, where a young “White-front” was taken and a pair of Lesser Canadas was caught, weighed, banded and released. Back into the air again, we reached Inuvik just at midnight. With the sun streaming down brightly from the northern sky it was a pleasant trip indeed. No need to hurry in this land of perpetual daylight, for activity is never hampered by darkness. Walt had his won special expression, which we all came to use frequently, “no need to hurry, we’ll get it done before the sun goes down.” By now Elizabeth and Viola had a nice flock of young birds to care for, and under their watchful supervision they were thriving beautifully. A check with Reindeer Flying Service disclosed they were scheduled for some work with the Reindeer herd and Walt and the plane would not be available for a couple of days. The herd, consisting of many thousands of Reindeer, is herded by natives and it was Walt’s job to fly these herdsmen from one location to another, depending upon their need. Inasmuch as operations were suspended until Walt and the plane were again available, we decided to spend the time at a lake about 12 miles north of Inuvik, where we could get our young birds out into pens, search about for birdlife and relax a bit. Tom Barry advised us there was a small cabin at the north end of the lake at which we could stay and suggested we do a bit of fishing. There was just enough time for Walt to shuttle us over before his flight to the Reindeer herd and in no time we were stowed away comfortably in the little cabin. The cabin itself was small – 12 by 18 feet, but it was solid, had tables and bunks and was quite comfortable. A tour of the area disclosed that birdlife was disappointingly scarce. A few Ptarmigan, a pair or two of swan, a few Arctic Loons and some ducks were all that were about. A small stream flowing northward from the lake, which was about two miles in diameter, was beautifully clear and cold. Since the southern two thirds of the lake was still encased in ice the waters were much too cold for bathing, as Jack soon discovered. It was a pleasant surprise to learn that the waters were abundantly filled with some very fine fish. Big Northern Pike lay right at the water’s edge – in the shallow water under the bushes. Arctic Greyling and Lake Trout were in both the lake and the small stream, as was a form of Burbot, and another very large fish of which, unfortunately, I have forgotten the name. These fish, which were as much as three fee in length, were built on rather graceful lines, similar to trout. They fed in schools and appeared to be rising to very small insects, probably mosquitos. No amount of enticing would induce them to take a lure, but since the schools were feeding at the surface and would swim very close to our rubber raft we did get a good, close look at them. Arctic Greyling, which we caught mainly in the stream, were very beautiful fish. Slenderly contoured, with a long, sweeping dorsal fin, they are perhaps one of the handsomest of all fresh water fish. In size they were quite uniform and most of the ones we caught weighed from 2 to 2 ½ lbs. They are unusually fine table fare. We caught Northern pike (locally known as Jackfish) ranging in length to 30 inches and Burbot of equal size. Almost all waters of the area abound in fish. It is truly virgin territory and would be a fisherman’s paradise. During our brief stay we spent a good bit of time discussing our project. One very obvious fact was apparent – a much more careful and detailed study of the geese at Old Crow Flats was necessary. Too many unusual conditions existed there to be merely coincidental. The Tule Goose, which has been known for more than fifty years in California, winters in small areas of that state where it secludes itself in isolated marsh situations characterized by heavy brush and timber growth. These brushy areas are shunned by the many thousands of other wild geese, including the common White-front, all of which choose the open marshes and fields. Only the Tule Goose prefers the bushy, timbered overflows. Here in the far north country we find a small number of birds utilizing just such a brushy wooded habitat at Old Crow Flats, while the vast majority of other wild geese were utilizing the more open tundra areas of the nearby coastal plain. This, in conjunction with the marked difference in the adult birds we had previously examined, convinced us that further work at Old Crow was necessary. In due time Walt returned to us, and it was once again “home” to Inuvik. Again a conference with Tom Barry, in which we discussed plans for a return visit to Old Crow Flats. Tom advised us that in the interest of banding some of the geese in that area, the Canadian Wildlife Service would allow us the use of their cabin there (which was just new), would pay the wages and transportation for Chief Charlie (as guide and consultant) and would furnish a thousand feet of nylon netting for use in trapping birds for banding purposes. This worked in beautifully with our own plans, so details were quickly arranged and a departure was scheduled for early next morning. Unfortunately, weather intervened and the fog banks again rolled in from off the polar sea to engulf the Richardson Mountains. It was quite impossible to get through and we were forced to idle the following four days, at a period when precious time was growing critically short. At long last, on July 13th, the fog lifted and once again we were off to the Flats. This time Elizabeth and Viola went along too. We utilized two planes to haul gear, the young birds and the passengers. Arrangements were for Walt, and the Cessna 170, to remain there with us, while the other plane returned to Inuvik. The flight over was most enjoyable and on the way we saw three Grizzlies and a number of moose. We landed at the cabin, a very snug and comfortable building with built in bunks, table, benches, cupboards and stove. Constructed of logs, with plywood floor and all neatly painted, it provided all necessities for a comfortable camp. As we were getting settled Walt flew to Old Crow village and returned with Charlie and as many tins of gasoline as the plane would carry. We were all tremendously impressed to learn that a 45 gallon drum of gasoline was amazingly priced at $295.00. Fortunately we were able to take it on a “return later” basis since gasoline prices at Inunvik was much less expensive. While Walt was gone I took time to set up my movie camera and got some footage of a Horned Grebe pair that had a nest about a hundred yards down the lakeshore from camp. Out toward the tip of land, on which our cabin was situated, was Charlie’s winter trapping camp. Here he had several canoes, two dog sleds and a pole tent frame. We later learned that he spent a good deal of time at this camp during the trapping season.

Several hours later Walt and Charlie returned. After a bite of supper, while Jack made a scouting excursion out along the lake shore, Walt, Charlie and I took to the air for a flight about the area. Charlie directed us to a fairly large lake on which he indicated we could expect to find flocks of moulting non-nesting birds. It was a short flight, but rather productive, since the birds were there just as Charlie had predicted. We did manage to put down and capture two swan cygnets to add to the growing flock of young birds back at the camp. On the way in we sighted a huge Grizzly, over which Walt made several passes. Like any Grizzly he soon became enraged and as we passed low over him he would rear up and make vicious swings with those great paws in an effort at retaliation. Charlie especially enjoyed this, though he cautioned us that Grizzlies were very dangerous. I am quite sure the bear was willing to verify the fact. During our time there we came to know Charlie well. He told us he was born in 1919 there at Old Crow Flats. He had lived his entire life in that general area and was, perhaps, more familiar with this country than any living man. He is a great hunter. From his father he learned the art of endurance. He is able to track down moose, caribou and even wolverine until they stop from sheer exhaustion – a remarkable feat. He often catches as many as 3,000 muskrats, as well as mink, foxes, beaver and wolverine during a trapping season. Although he has never been to school he has taught himself to read and write, not only his native language, but the English language as well, which he handles fluently. His family (12 children) is a source of great pride. His eldest son is a ski champion, having won many trophies in such far away places as Colorado and British Columbia. His daughter is stationed in the hospital and younger children are attending school. Charlie insists they have the education he was never able to obtain. Despite his lack of formal schooling he possesses an exceptionally keen mind, is amazingly well informed and is truly a wonderful person. Many happy hours were spent visiting with him. We constantly bombarded him with questions, each of which he answered patiently and thoroughly. It was a privilege to know him, a truly great man. Because time was now very short it was necessary to work long hard hours, if our work was to be completed. In order to make good catches for banding it was now necessary to use the nets which Tom had furnished. The procedure was to spot a flock of geese from the air (flightless due to the moult) then choose a spot along the shore where the nets could be set. The netting, which was much like poultry wire except it was made from light weight nylon, was about 5 feet in width and nearly a thousand feet in length. A location was chosen for the placement of the nets where the geese could leave the water and get up onto the shore easily. The netting was placed in such a manner as to form a fence with two wings in the form of an inverted V. At the apex a small round holding pen was built so that the geese, as they left the water and came up onto the shore, would be funneled into this round pen where they could be held while they were weighed, measured, sexed and evaluated. The task of setting the nets was formidable indeed. The heavy brush was a constant problem, for it was very difficult to get the netting to drape on the ground properly so that birds couldn’t slip under and away. The filmy nylon tended to drape on every bush and shrub and get it down at the bottom. To complicate matters, stakes to be used as posts to hold the netting, could not be sunk deeply enough into the ground to hold. In much of the area the permafrost was a scant 3 to 6 inches below the surface, leaving only the mounds of moss above the frozen ice to hold the stakes. At best it was flimsy construction, but under existing conditions we could do no better, so it had to do. At this point it might be well to mention the mosquitoes. Our other expeditions into the far northern tundras had found them to be amazingly free of these pests. Here, however, the exact opposite was true. No matter where we went they were there in unbelievable clouds and made work an absolute torment. They would alight on us in such swarms as to be almost solid. We were forced to wear heavy clothing at all times, which, in the 80 degree heat was at best burdensome. Repellant offered token resistance only. We came to despise the mosquitoes. Once the nets were read a man was concealed beyond the tip of each wing. Walt, under Jack’s supervision, would then take the plane out and begin herding the geese in toward us. This could be done because flightless geese tend to band closely together in the water and can be herded just like sheep or cattle. The secret was not to crowd them too closely, which forces them to dive and become scattered. Under Jack’s supervision Walt soon became very proficient at driving them with the plane, simply by taxiing along behind them — much as a man drives cattle with a good horse. As soon as the geese are put ashore they run rapidly away from the plane, directly into the mouth of the net. At this time the wing men expose themselves at either end of the net, the plane is beached and made secure, and everyone takes a hand in driving the birds into the round holding pen. Due to the difficulty encountered in properly setting the nets it was found that perhaps 60% of the birds brought into the enclosure were able to affect an escape, usually by ducking under, but occasionally over the top too, thereby cutting our take considerably. Despite the difficulties encountered we were able to capture 50 of these geese, which were subsequently banded, weighed, measured, evaluated and released. Not an impressive number, perhaps, but in view of the near impossible conditions it was not a bad showing either. As all things must end thus our stay at Old Crow Flats came to a close. It was back home to Old Crow village for Charlie and a return to Inuvik for us. From Inuvik it was soon to Edmonton – the DC-6 is very fast, and thence to Big Timber. The great expedition was over. With actual field work completed the task of evaluation was now before us. As might be imagined the questions foremost in everyone’s mind were, “Had the expedition actually fulfilled its mission?” “Had the nesting ground of the Tule Goose been discovered?” and “Had birds been taken for a propagational program?” An immediate answer could not be given. Although the expedition had returned with 5 young and 3 adult birds an immediate evaluation could not be made. Since the adult geese were in full moult it was completely impossible to take measurements, one of the key factors in differentiating between the common White-fronted Goose and the Tule. More over, since downy young of the Tule sub-species has never been described, we had no material for comparison with the 5 young birds we had taken. Further time was required before these questions could be resolved. As this is written (early October 1964) we are now able to furnish many of the answers for which we have been waiting. As the three adult birds have emerged from the moult, and as the 5 young have developed, much pertinent data has been compiled. Generally speaking the eight birds definitely answer the description of Tule Geese. Certainly the dark color is there – especially the brown heads and necks. The long heavy bills, one of the distinctive features of the Tule are strikingly exhibited. The large wings and body weight of the Tule are also characterized. In view of this evaluation it would appear that the expedition has terminated successfully and that the nesting grounds of the Tule Goose has been found.

~ Part Two In Search of the Tule Geese – Part 2 Editor’s Note: We have received many letters commenting favorably about the article “In Search of the Tule Goose” by Bob Elgas which appeared in the January issue of MGB (Modern Game Breeding). Realizing that there is a great reader interest in this typ northern expedition, we have attempted to prepare additional material. We hope that you will find this “follow-up” story equally enjoyable. I am certain that, for as long as I live, whenever I hear a flag “whipping” in the wind or the fasteners on the halyard “clanging” against a metal mast, I shall go back in memory to the front yard of the Alexander McKenzie School, Inuvik, Northwest Territory, Canada. For each day that Bob Elgas and I trudged our way, bucking the brisk wind toward Reindeer Flying Service, we passed this flag pole. The dark ominous clouds scurrying overhead, combined with the whipping and clanging at the flag was sufficient evidence that we couldn’t fly to Old Crow Flats that day. Yet, impatient creatures that we are, we had to be told “officially” by our pilot Walter Goulet. It was this kind of blustery weather that was to be indelibly imprinted on my mind. All during our trip in search of the Tule Geese, the capricious Arctic climate was to stand as the principal obstacle to our travel. Distances are so vast in the northland that travel on foot is hopeless. But the airplane has compressed time and space. Naturally, when the weather prevented flying, it halted our search. Over the centuries such obstacles have taught the Eskimo and Indian patience and these hours, are happily wiled away in family activities. To them, tomorrow the weather will be better. To the impatient members of the Tule Goose Expedition these delays were exasperating.